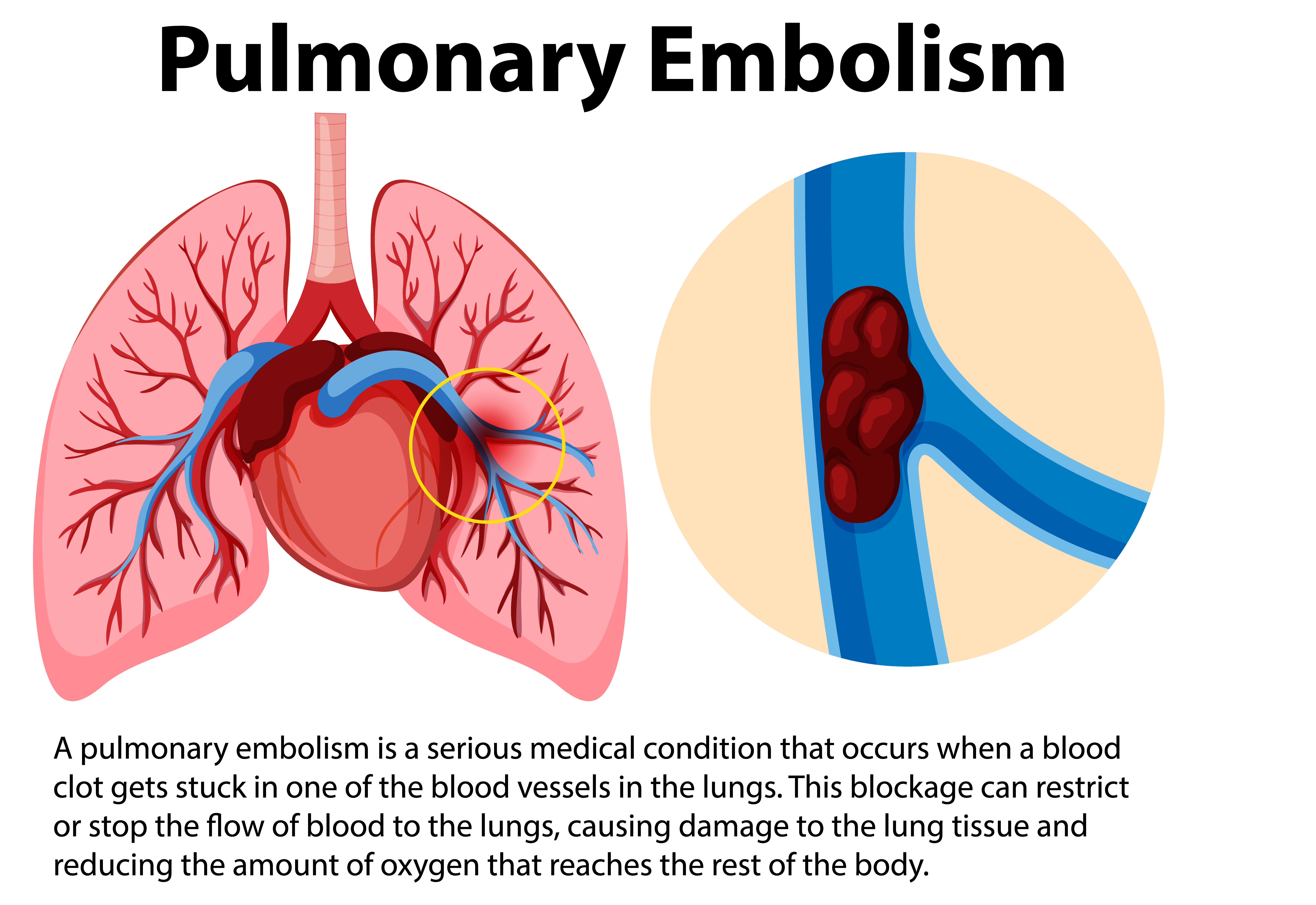

A pulmonary Embolism (PE) is a blood clot that lodges in the lung arteries. The blood clot forms in the leg, pelvic, or arm veins, then breaks off from the vein wall and travels through the heart into the lung arteries. Most PEs are due to pelvic and upper leg blood clots that first grow to a large size in the vein before detaching and traveling to the lungs. PE can cause death or chronic shortness of breath from high lung artery pressures (“pulmonary hypertension”). PE can impair heart muscle function, especially the right ventricle, which pumps blood into the lung arteries.

Most of the people who die from a pulmonary embolism do so within 30 to 60 minutes after symptoms begin.

What is Pulmonary Embolism (PE)?

Symptoms

The most common symptom is unexplained shortness of breath and/or chest pain with difficulty breathing. However, PE can be difficult to diagnose and has been called “The Great Masquerader.” It can mimic pneumonia, congestive heart failure, and a viral illness known as pleurisy.

Shortness of breath

Chest pain, often worse when taking a breath

A feeling of apprehension

Sudden collapse

Coughing

Sweating

Bloody phlegm (coughing up blood)

The signs and symptoms of these disorders can vary by individual and event. Some individuals may also experience uncommon symptoms such as dizziness, back pain or wheezing. Because PE can be fatal, if you experience these signs or symptoms seek medical attention right away.

A definitive diagnosis of PE must be made in a hospital or clinic with radiology facilities. A chest CT scan (“CAT scan”) or a nuclear medicine scan are the most common tests to diagnosis PE. The most crucial point is for patients and their health care providers to consider the possibility of PE. Prior to a chest CT scan or a nuclear medicine scan, doctors may determine the likelihood of PE through screening tests such as a chest X-ray, electrocardiogram and a blood test called a “D-dimer” (low D-dimer levels virtually exclude PE).

Diagnosis

The foundation of treatment is thinning the blood with anticoagulants such as heparin, low molecular weight heparin, fondaparinux, direct thrombin inhibitors (argatroban, lepirudin, or bivalirudin) or the oral blood thinner, warfarin. Immediately acting intravenous or injected blood thinner must be administered right away. The oral blood thinner, warfarin, takes about five days to become effective to prevent the development of a recurrent PE.

In addition to blood thinners, more aggressive therapies include “clot buster” drugs such as TPA or catheter-based or surgical embolectomy to remove the PE.

The duration of treatment with the oral blood thinner will vary from 6 months to lifelong, depending upon the circumstances of the PE and other individual risk factors.

Treatment

Prevention of PE is a lot easier than diagnosis or treatment. Therefore, when hospitalized, it is important to ask your health care providers what measures are being taken to prevent PE. These can include the use of graduated compression stockings or prescription of low doses of blood thinners such as unfractionated heparin, low molecular weight heparin, or fondaparinux.